An important book from Morgan Housel called “Same as Ever”

Somebody, make me a time machine

Life would be easy if we had a way to accurately predict the consequences of the events/ actions.

Scenario 1 – what would be your reaction if some random person hands you a $1,000,000 lottery ticket and, in few moments, you realize that you just won that lottery?

Scenario 2 – what would happen if an ambitious project that you worked on tirelessly for many years while sacrificing your other priorities – ends into a big failure because of a seemingly impossible and insignificant event/ error?

For most of us these two scenarios are practically impossible but the odds are still non-zero. They can happen in reality.

How can we be sure that they selectively happen to certain person? Scenario 1 for ourselves and Scenario 2 for our enemies especially… (Just kidding)

If you closely observe the lives we are living right now, you will see that we are always oscillating between such events which demand certainty of outcomes even before the are realized. We have this innate urge to remain ready for such events; it is what we are always striving for.

Now, one question – are we living in a matrix? Is universe a simulation?

If the answer is ‘YES’, then it means that every outcome should be predetermined. If everything is predetermined then why things don’t happen the way we ‘want’? Does that mean that we lack the computational capabilities to precisely calculate the outcome? OR is what is destined to happen different from what we ‘want’?

If the answer is ‘NO’, then everything explodes into meaninglessness. The answers are nihilistic.

Looking at the both outcomes of this question we see that we need a baseline to make our decision making effective. Is there a formula to systematically put all the things happening around? What are somethings in nature whose knowledge will ensure our satisfactory existence. (I am being very optimistic while writing ‘satisfactory’ word here.)

In simple words, what is the formula to live a good life? whether it is predictable or not.

Morgan Housel the famous author of the Psychology of Money wrote one important book called Same as Ever which tries to answer this same question. Same as Ever drives the motto of objective flexibility and subjective awareness of every event happening around us and with us.

This is a deep dive into Morgan Housel’s book “Same as Ever”.

I will try to keep this short. Here are some instructions:

Those who have read this book – each idea in this book is numbered in the sequence Morgan explains in the flow of the book. So, #1 is Hanging by a Thread as mentioned in book and #23 is Wounds heal, Scars last

Those who haven’t read the book – I have given short summary of what Morgan discusses in each of the 23 ideas. That should help you to wrap you head around my distilled down version of this book.

(I apologize for putting that part in the end and spoiling the conclusion/ discussion on this book.)

I would say this book has been one of the most important books I have come across. (I am an average book reader by the way. So, not sure if same would be the case for other people.) While going through each idea, you will realize that something keeps on repeating; and even though it repeats, it brings new perspective into that specific discussion. My attempt to summarize this book focuses on picking what is common but connected to all the facts mentioned in the book and also their connection to the reality we live in.

Discussions

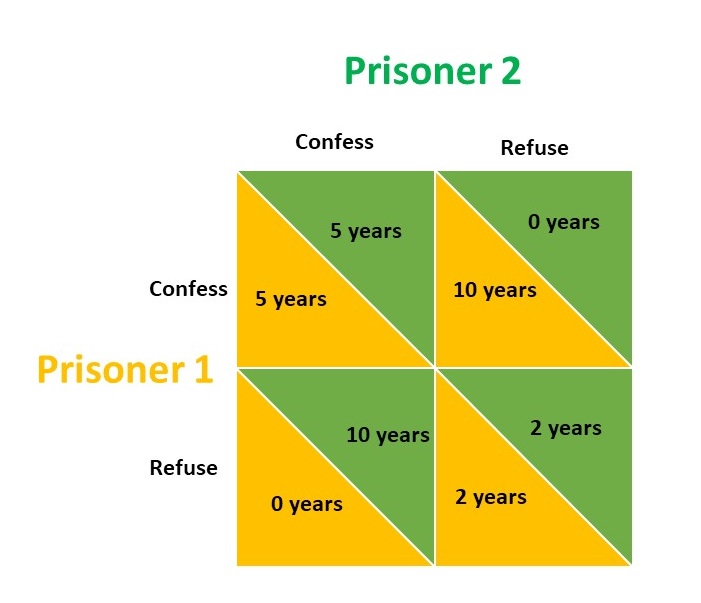

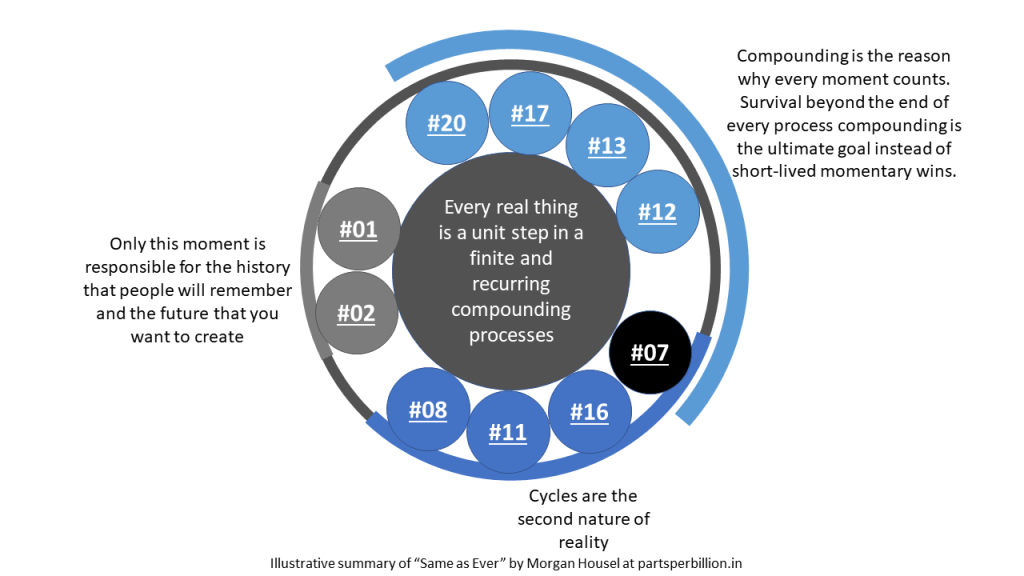

The discussion is in 3 steps, so adjusting our understanding to previous step is key to understand the next step. The illustrative images in each step of the discussion connects the ideas from the book to a common central idea. It will be handy if you read this with the book in your hand or you can jump to the point-to-point summary (the part after conclusion) in a neighboring tab of your web browser.

Step 1 discussion:

You will see in the figure 1 that reality is ever changing process of infinite real events. The key to understand what is happening is to see every event containing same potential at first. Keep in mind – same potential – neither good nor bad. Once you assign every event with equal potential you will see that compounding accounts for that single event to build on and create the next event. Sometimes two big events will compound together to create an enormous event.

Now comes the fun part – the enormity of every compounded event will always be in favor of someone and against the favor of the complementary population. This makes that event good or bad for people. Some will suffer some will rejoice.

A person who knows how the world, nature or universe works will not have preferences, favor-ability towards such events. The answer lies in the cyclical nature of such events. Keeping a single event sustained for long duration demands to go many things to work in supporting ways and as every event has same potency in the infinite possibilities, it surely will lead to the downfall of that process. It’s just matter of time.

Talking about matter of time – the game of life is not about winning, rather it is about remaining in the game longer as the compounding pays off and decomposes into new start.

Our limited life span intuitively doesn’t allow us to wait till the compounding pays off. That is exactly where we make mistake. That is exactly why we are devastated by a single seeming insignificant event causing destruction of our favorite things.

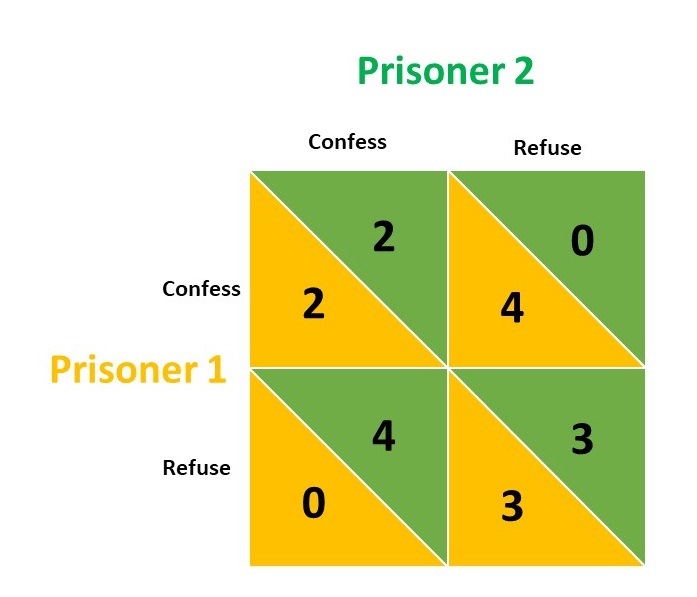

Step 2 discussion:

Our urge to predict everything to ensure survival demands perfection in every entity considered for precision and accuracy of prediction. As reality is made up of many real possibilities, this count of possibilities and the errors associated with their measurements require huge resources which render the prediction process impractical for the possible outcomes.

(Keep in mind right now that we are only talking about those variables, events which we can understand; we haven’t even entered into those variables, events we don’t even understand or know in first place.)

The moment we introduce poorly known, immeasurable but significant variable – the whole game of predictability crumbles down.

That is exactly why instead of striving for better predictability, it is a smart choice to be prepared for everything. Knowing that this too shall end soon should comfort us to prepare for such things/ events. The rejection of the urge for perfection, absoluteness and full efficiency will immediately prepare us for everything that reality unfolds.

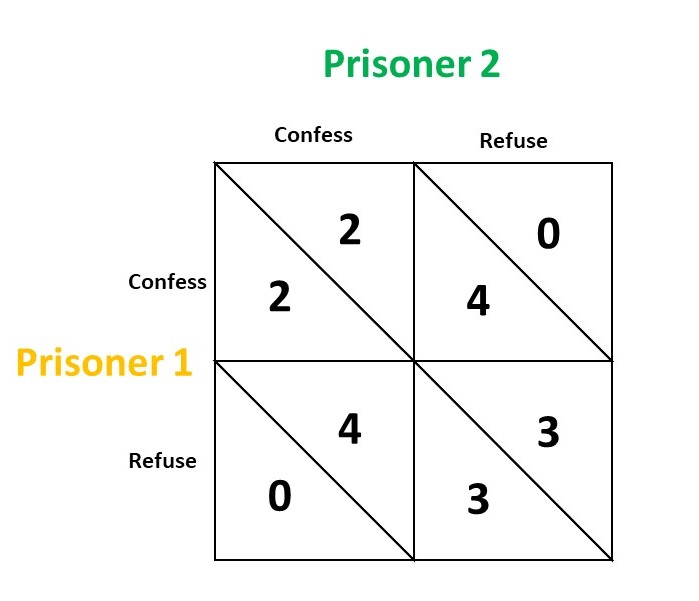

Step 3 discussion:

Now that we know how every event is potent and can immediately contribute to a cyclical process of compounding, it is important to understand how we comprehend that compounding. As everything that we do is directly linked to our survival we are by default born with preferences. These preferences get eliminated or amplified based on the life experiences we have. Even though our urge for predictability demands objectivity we often forge the subjective parts of every narrative. The subjectivity is important, because the reasons to survive are different for different people.

Conclusion – Human behavior and laws of nature

Our mind rarely understands anything as a flow of entities. Almost all of the fundamental entities existing in nature are flow – continuum entities. But in order to understand them study them we break them into pieces which makes is practical to quantify and predict. For time as an example – we have past – present – future; we need this separation to comprehend the flow of time. This slight arrangement of separation of events just for the convenience of communication and comprehension for our minds has now become such a second nature of our realities that we could hardly come out of the idea of past and future. Past keeps on haunting and future creates anxiety due to the uncertainty. Nostalgia from past brings us joy and what advancements future will present inspires us to work harder today. We rarely notice that this works both ways.

It is really difficult and impractical for our mind to let go of this past-present-future mentality. This convenience of separation for the sake of improving our decision making and survival has imparted a sense of time being a set of discrete isolated events, independent events. This steals the feature of hyper-connectivity in our understanding of reality.

Once we come out of the discretization of time as past-present-future we will see that every event is equally important and highly interconnected and multidimensional (in the sense that it creates multiple real effects on multiple entities) Our mind being biased for survival and in energy optimization mode, it always focuses on what is required to remain alive. This sense of remaining alive now has evolved into intellectual survival – as in what things we define as our life. So, even though from objective point of view all events remain exactly the same, on our personal level certain events are highly important because they change the things we are attached to in a drastic way – in most cases our life. We are now scared to die intellectually – a mental death – the death of our truths – our identity. And trust me, this happens frequently.

Morgan in this book very beautifully noted down the factual version of the reality we live in; it is beautiful because it shows how our human nature is always affecting the seemingly objective reality of the most of the things.

This is my ultimate distilled down version of the book “Same as Ever” by Morgan Housel.

It also highlights that our mind is the first and the easiest one to fool, which leads to false sense of superiority over others and creates biases. Once we accept that nothing is perfect, no one is perfect – it injects humility and forgiveness. It also makes us grateful for what we possess today. What else could be more important than this to be justified as a human being?

These points ask for detachment from predictions and end results. A sense of responsibility for the actions could be the best version of any person – this exactly is invoked when we are trying to prepare for the future instead of striving to predict it.

I think we need more ideas like this when we are fighting for survival for such unimportant things where we already know the real, practical answers but have decided to ignore them.

The ability to see every event at the same level is a superpower any one of us can have.

For those who haven’t read the book here is the point-to-point summary of the book “Same as Ever”:

#1. If you know where we’ve been you realize, we have no idea where we’re going.

Here, Morgan gives many real-life events where a single decision led to catastrophic events causing loss of many lives and valuable resources.

When we study history even when we know what exactly happened, it is tricky to pinpoint the trigger for that event. There will be why and how behind every small-small event and when we will reach to its origin it becomes really difficult to wrap your mind around that petty thing which had led to such a big and historic event.

The absurdity of past connections should humble your confidence in predicting future ones.

#2. We are very good at predicting the future, except for the surprises – which tend to be all that matter

In very simple words, Morgan highlights the extents of our imagination and thinking. Even though they are infinite, the nature in which we are existing is equally or rather infinite in bigger and greater sense. That is exactly why even when we think we are prepared for everything, nature will always have something new in its pocket to reveal and not being ready for that exact new thing makes that event overwhelming for us because we were not ready for that exact new reveal.

It’s impossible to plan for what you can’t imagine, and the more you think you’ve imagined everything the more shocked you’ll be when something happens that you hadn’t considered.

This itself should humble us. That is why preparation is more important than forecasting.

Invest in preparedness, not in prediction

#3. The first rule of happiness is low expectations.

The most important observation Morgan puts here is in the ways we gauge our resourcefulness – it is always relative – material or immaterial – objects or emotions. We always have a baseline which is created by comparing ourselves with those around us. That is exactly why we rarely appreciate what we have at our hands.

We always crave for what ‘they’ seem to have instead of appreciating what we already and really have in our hands. Even when we are unsure about whether others actually have those things, still we crave those things for us, which is tragic!

Morgan expresses that almost all of the truly precious things in our life don’t come with a price tag that is why we never care to evaluate their importance – like good health, freedom. Same is the case with expectations.

When Morgan is asking for low expectations, it is not omission of the motivation to improve ourselves. Low expectations ask for realistic expectations. One must always be observant of the gap between what we wanted and what happened in reality.

#4. People who think about the world in unique ways you like also think about the world in unique ways you won’t like.

Here, Morgan talks about the role models, heroes, leaders we consider the best of us all. It is very important to understand that they are the best among us all because they did something in very exceptional manner which made them stand out of the well-defined ‘boring’ and ‘average’ structure of the society. If they would have followed the same paths that other followed, they would have been just like others.

In order to stand out of the masses they did something different.

Now be cautious! This different could be seen as good or bad as per the average crowd level. And keep in mind this specialty in that person is because others don’t have it in them. So, in order to create and develop something special out of the same average crowd one has to overcome a resistance of the masses where a trade-off is done with other aspects of their personality. Sometimes the exceptional conditions create exceptional personalities which many people fail to recognize.

Of course they [successful people] have abnormal characteristics. That’s why they’re successful! And there is no world in which we should assume that all those abnormal characteristics are positive, polite, endearing, or appealing.

Simple words, there is always some trade off to achieve something truly exceptional.

You gotta challenge all the assumptions. If you don’t, what is doctrine on day one becomes dogma forever after

#5. People don’t want accuracy. They want certainty.

A common trait of human behavior is the burning desire for certainty despite living in an uncertain and probabilistic world.

Morgan discusses how we are always trying to alleviate the bad results, pain in all life scenarios. The urge to survive supersedes everything. Our brain always wants a confirmed trigger on whether to fight or flight for given problem. It is always in energy optimization mode and in the uncertain world filled of infinite possibilities it wants something to act on immediately. Otherwise, brain knows that it won’t survive. The urge for certainty – that clarity of whether to fight or flight is the most important information than how precisely we are assessing the reality. It’s like brain takes a shortcut to ensure survival. That is exactly why huge load of information especially numbers overwhelm us.

The core is that people think they want an accurate view of the future but what they really crave is certainty.

#6. Stories are always more powerful than statistics.

If we continue the train of thoughts from previous point, soon we will appreciate how dearly we appreciate stories instead of boring numbers. Even when stories would tell a lie and numbers would tell the real, pure truth we would always choose a fake story over realistic numbers. Our brain doesn’t want to overwork itself to ensure survival.

Good stories tend to do that [evoking emotions and connecting the dots in millions of people’s heads]. They have extraordinary ability to inspire and evoke positive emotions, bringing insights and attention to topics that people tend to ignore when they’ve previously been presented with nothing but facts.

Stories create an emotional, empathic bridge between people which our brain already knows since the childhood. The very first think a baby does to start breathing is crying not counting. (I know the analogy is lame but it works here) we are implicitly trained to actively process emotions first and then numbers. Stories enhance this ability on next level.

That is exactly why emotional-ity will always be preferred over rationality.

We live in a world where people are bored, impatient, emotional, and need complicated things distilled into easy-to grasp scenes.

#7. The world is driven by forces that cannot be measured.

Morgan brings here more clarity on the objective nature of the numbers even when they are showing the truth, the reality. The point that our reality is made up of the infinite possibility itself shows that the sheer limitation of our computation capability will create a partial picture of the bigger reality. This happens because many of the factors which influence our reality are beyond quantification. That is exactly why whenever we are making any decision based on objective and true data (like truest of true numbers) we should bear in mind that these numbers are not accounting for those unmeasured factors which also affect the reality we are trying to understand.

Some things are immeasurably important. They’re either impossible, or too elusive, to quantify. But they can make all the difference in the world, often because their lack of quantification causes people to discount their relevance or even their existence.

In simple words, our story loving brain is driven by intuition and safe/ familiar information which is unquantifiable most of the times.

#8 Crazy doesn’t mean broken. Crazy is normal; beyond the point of crazy is normal.

Morgan is trying to point out how we understand what is means to be at the top. He established that most of the tops we experience in life are to because we have experienced falling down from them and we would have never understood that we were at top unless we have had fall down from them.

The only way to discover the limits of what’s possible is to venture a little way past those limits.

We never appreciate summit of something unless we start climbing from down or fall down from that summit. That is exactly why what made you feel at the top will make you safe and that attachment to safety will lead to your fall, the pain of fall will motivate you to climb new heights and again the cycle will go on.

#9. A good idea on steroids quickly becomes a terrible idea.

Morgan here explains how evolution created the species around us. There was always some trade-off while evolving because of the forces of nature. In nature nothing has absolute competitive advantage otherwise a single species will take over everything that single species alone will lead to its downfall and destruction due to the lack of diversity.

Most things have a natural size and speed and backfire quickly when you push them beyond that.

In simple words, anything that is burns bright, goes out fast. Resources behind every process are limited and even if they would be available in surplus, extent of their utilization affects the outcome and overall integrity of that process.

#10. Stress focuses your attention in ways that good times can’t.

The urge to survive makes our brain to push to its untested limits. These limits are there just for the optimum behavior so that our brain could actually use the reserve energy when it is the question of life and death. When it come down to do or die – people have always delivered in surprising and shocking ways.

The circumstances that tend to produce the biggest innovations are those that cause people to be worried, scared, and eager to move quickly because their future depends on it.

Morgan points out here that this stress should be healthy because there is always a natural size of everything as explained in point #9.

There is a delicate balance between helpful stress and crippling disaster.

#11. Good news comes from compounding, which always takes time, but bad news comes from a loss in confidence or a catastrophic error that can occur in a blink of an eye.

Growth always fights against competition that slows its rise.

Morgan here shows how things that exist today as our reality have gone through multiple iterations. They have already failed many times and started again long ago; its just that the compounding imparted grandeur and power to fight against the adversities of the life which made their realisation possible here in front of us. There will again be some simple, seemingly insignificant event which will destroy this creation and things will start again.

To enjoy peace, we need almost everyone to make good choices. By contrast, a poor choice by just one side can lead to war.

#12. When little things compound into extraordinary things.

Here Morgan points out from the examples of history how in order to avoid a big calamity people ignored some small incidents which led to even bigger calamities. It is ingrained in our mind to overlook big events because the smaller events which lead to their realization are “small and insignificant”.

Small risks weren’t the alternative to big risks; they were the trigger.

#13. Progress requires optimism and pessimism to coexist.

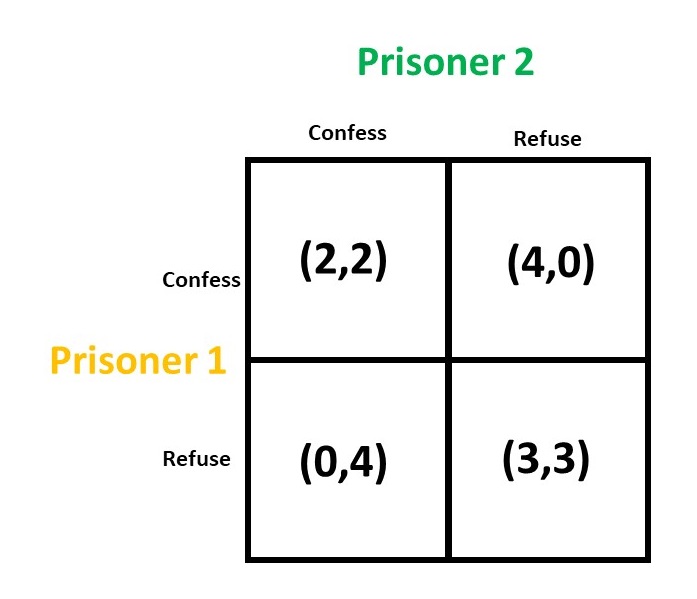

Morgan here talks about how our preferences for each and everything have stolen away the realism in our lives. Instead of favoring one side, life is more about appreciation of the spectrum. It was never about who wins or who loses because both are short lived. It is always about who survived and stayed in the game longer. (Simon Sinek calls it the infinite game as explained in Game theory.)

The trick in any field – from finance to careers to relationships – is being able to survive the short-run problems so you can stick around long enough to enjoy the long-term growth.

Whoever lives to see the end wins but that victory is just over those who couldn’t survive. There will always be some room at the top because conditions never remain the same.

#14. There is a huge advantage to being a little imperfect.

The more perfect you try to become, the more vulnerable you generally are

The idea of perfection immediately steals the flexibility from any given system. Because of the perfection the system is bound to certain thriving conditions and exactly when you expose this system to the reality of infinite possibilities there will always be some ‘seemingly’ trivial event which will take down that whole system.

A little imperfection makes the system to bend thereby giving place to perform in unimagined conditions and as we have already learnt that the reality is full of unimaginable but real events.

Morgan beautifully explains the ways in which natural evolution has worked out.

A species that evolves to become very good at one thing tends to become vulnerable at another.

…species rarely evolve to become perfect at anything, because perfecting one skill comes at the expense of another skill that will eventually be critical to survival.

Nature’s answer is a lot of good enough, below-potential traits across all species.

#15. Everything worth pursuing comes with a little pain. The trick is not minding that it hurts.

The really important and actually valuable things in life don’t come with a price tag and that is exactly why we are not ready to pay any price. This makes our minds to wish for such things because of the false sense of entitlement. This same entitlement blinds us from the real actions which can lead us to this achievement and we keep on whining about not achieving these things. A wishful thinking!

A unique skill, an underrated skill, is identifying the optimal amount of hassle and nonsense you should put up with to get ahead while getting along.

#16. Most competitive advantages eventually die.

A we have now already understood that even a small event can lead to collapse of any grand creation and how easy it is to undermine any event we must now accept that nothing big will stay as it is now. Same goes for any competitive advantage. As things keep changing the advantages which made their impact big will become irrelevant with the changing things. One has to keep on reinventing in order to remain relevant and effective with the changing times.

Evolution is ruthless and unforgiving – it doesn’t teach by showing you what works but by destroying what doesn’t.

#17. It always feels like we’re falling behind, and it’s easy to discount the potential of new technology.

Morgan highlights how the innovations which we consider ground-breaking, world-changing were result of multiple small-small events creating synergy to coexist.

It’s so easy to underestimate how two small things can compound into an enormous thing.

#18. The grass is greener on the side that’s fertilized with bullshit.

You never know what struggles people are hiding.

As we have already seen our urge to compare our conditions with the conditions of others and always consider ours to be the worst most of the times, it is evident that we are experts in judging everything in its entirety based on very little information. Our biases and basic mentality feed this tendency furthermore. But reality is always like the iceberg.

Most of the things are harder than they look and not as fun as they seem.

#19. When the incentives are crazy, the behavior is crazy. People can be led to justify and defend nearly anything.

Morgan here shows that beyond envy people are driven by incentives. You can make people do almost anything, make them believe them in almost any thing if their interests are aligned in that. This is strong when people are helpless and when it is about their survival.

One of the strongest pulls of incentives is the desire for the people to hear only what they want to hear and see only what they want to see.

The beauty that Morgan points out is that this can also be used to bring good out of people.

It’s easy to underestimate how much good people can do, how talented they can become, and what they can accomplish when they operate in a world where their incentives are aligned towards progress.

#20. Nothing is more persuasive than what you’ve experienced first-hand.

As we have emotional beings and we have already seen that we will always prefer emotional clarity of falsehood over the numerical, arithmetic truth it shows that every part of our understanding of life is tied to our own individual experiences. We rarely appreciate the foretold truth. But we will appreciate all those things which we experience on our own.

That is also why there are certain truths which very few people have experienced but are not generally accepted by the masses because there is no part to connect personally. We can only connect personally only when we have passed through those experiences.

That is exactly why it is difficult to convince people of something really exceptional and extraordinary personal experience, that also why it is also easy to fool people.

The next generation never learns anything from the previous one until it’s brought home with a hammer… I’ve wondered why the nest generation can’t profit from the generation before, but they never do until they get knocked in the head by experience.

#21. Saying “I’m in it for the long run” is a bit like standing at the base of Mount Everest, pointing to the top, and saying, “That’s where I’m heading.” Well, that’s nice. Now comes the test.

In simple words, Morgan shows us that we rarely will ever know what we have signed up for. Most of the times our simulative experiences and thoughts will be broken down by the unimaginable possibilities of the reality. Instead of craving for that summit one must try to stand strong while they have started this journey and remain faithful to this step they are taking ahead. This attitude has to be kept with every step which very few people maintain.

Long term is less about time horizon and more about flexibility.

#22. There are no points awarded for difficulty.

Almost all of the times people appreciate certain things, certain people because they couldn’t not have or become like them. This crates a mysticism. We are always attracted to mystical things because the urge to know better (to improve chances of survival against unknown) is our hidden trait.

Complexity creates this mysticism instantly. That is why we most of the time reject truths which are so obvious and in front of our eyes and accept that intellectually stimulating complicated lie. The complexity makes our brain to actively engage in that thing which creates an attachment just because our brain was invested in it.

Complexity gives a comforting impression of control while simplicity is hard to distinguish from cluelessness.

#23. What have you experienced that I haven’t that makes you believe what you do? And would I think about the world like you do if I experienced what you have?

Morgan points out that our lives even though we have common experiences, we associate ourselves to certain groups, certain ideologies on deeper levels and at core we are totally different and individual.

Many debates are not actual disagreements; they’re people with different experiences talking over each other.

References:

- Morgan Housel’s book “Same a s Ever”.

- Morgan Housel